Legends

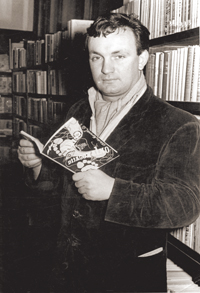

LIBERO MARKONI (1928-1990), THE UNFORGETTABLE POET AND GUARDIAN ANGEL OF HIS CITY

The Bohemian Prince of Čubura

The absolutely unavoidable place in the ”local mythology” of the Serbian capital belongs to Slobodan Marković, the one who wrote ”Seven Midnight Tales through the Keyhole”, ”Anabel Li”, ”Once in an Unknown Town”, the painter and journalist whom people used to call ”the bohemian with the bow tie” and ”the kind sorcerer”, the one who rests next to Miloš Crnjanski. ”He passed through our life, our literature, journalism and painting, leaving a trace like a giant ship that enters the port by plowing the sea.” The magnificent talent, caped in irresistible charm and dense veil of love, knew how to make a celebration out of everything

By: Branimir Stanojević

Libero walks the Belgrade streets, passing by buildings bending under the fierce strokes of wind like reed in the shrubbery, wearing a short navy blue coat with two rows of shiny buttons, the one wore by sailors in all ports, flocks of birds land on his wide shoulders and bring him morning news from all parts of the world. A small exalted bird, very lively, with charming moves, with a good dose of pathos, recites him the latest verses of Okujava and the favorite verses of Yesenin, Mayakovsky, Akhmatova… Corpulent as he is, with a high forehead, with the posture of a winner from many storms, with a wreath of thorny roses on his head and in his heart, he passes the square which today carries his name and goes sharply down towards the ”Borba” editorial office. In his pockets, he carries new articles about the world and people as he sees them, and the resolution of a writer in a constant and unyielding war against all who want to deprive him of a part of freedom, difficultly conquered and jealously preserved. He used to watch people with a curious eye, in an unusual and kind manner, occupied with the good, aware of the bad, that dreamer, that sorcerer, and previous prisoner of the concentration camp in Smederevska Palanaka (1943) while he was a boy. Libero walks the Belgrade streets, passing by buildings bending under the fierce strokes of wind like reed in the shrubbery, wearing a short navy blue coat with two rows of shiny buttons, the one wore by sailors in all ports, flocks of birds land on his wide shoulders and bring him morning news from all parts of the world. A small exalted bird, very lively, with charming moves, with a good dose of pathos, recites him the latest verses of Okujava and the favorite verses of Yesenin, Mayakovsky, Akhmatova… Corpulent as he is, with a high forehead, with the posture of a winner from many storms, with a wreath of thorny roses on his head and in his heart, he passes the square which today carries his name and goes sharply down towards the ”Borba” editorial office. In his pockets, he carries new articles about the world and people as he sees them, and the resolution of a writer in a constant and unyielding war against all who want to deprive him of a part of freedom, difficultly conquered and jealously preserved. He used to watch people with a curious eye, in an unusual and kind manner, occupied with the good, aware of the bad, that dreamer, that sorcerer, and previous prisoner of the concentration camp in Smederevska Palanaka (1943) while he was a boy.

Between his first book, After the Snows, published in 1949, and his last one, Southern Boulevard, and his death in Belgrade in 1990, the time that elapsed was marked with constant writing, drawing, painting and traveling, without which he couldn’t do. And all this found its place between the covers of more than sixty books.

Those who entered his artistic workshop in order to make a list of everything he created, which is certainly an impossible task, using the language of statistics recorded the following: thirty two books of poetry, nine books of prose, five dramas, three travel itineraries, three movie and television scripts, four books of reportages, twelve books of translated poetry, two anthologies, one book about cookery, one book of essays… And how many texts are scattered in numerous anthologies, magazines and newspapers, when it is known for certain that he cooperated with more than 160 editorial offices? As if, just like that, he spilt around himself pearls of words and smiles. How would he, tousled as he was and always ready to laugh, react to such an arid list of his life? There would be roars and loads of laughter, witty remarks, lucid observations...

Gold Diggers, Co-Travelers, Itineraries, Belgrade These Days, the Čubura Observatory… Those were series of articles, unimaginable today, for which readers of newspapers excitedly awaited a new day.

His masterly drawings, very unusual, which are and aren’t sketches, luxurious in their simplicity, extraordinarily rich for their charge, a simple and magic story about the object of writing, sufficient to themselves, but always accompanied with a text, represented a magical formula which enables one to see the world around exactly as it is, both good and bad, both sweet and bitter, both gentle and rough.

The number of countries he visited with his pencil and pen, leaving behind traces of texts and drawings, is something no one could ever count. He was the only one who knew that map of friendly spots scattered all around the planet. It was hidden somewhere in his eye.

You understand with your heart and know the language just enough to create the most beautiful translations of Yesenin’s poems, to peek into every corner of Thessalonica and Istanbul, to form a web out of your footsteps in the Asian steppes and sleepy cities such as Alma Ata or Samarqand, to fully breathe the air full of salt and secrets in Odessa, to make yourself at home in Kiev, Moscow, St. Petersburg.

IN THE NIGHT OF THE SNOWSTORM

Who wrote the most beautiful articles about Mount Athos, at the time when people didn’t travel there often? In those times, he received significant journalism and literary awards for those itineraries, and the monks of Mt. Athos used to say that a more honorable person hasn’t stepped into that empire of solitude and soul for a long time. Who wrote the most beautiful articles about Mount Athos, at the time when people didn’t travel there often? In those times, he received significant journalism and literary awards for those itineraries, and the monks of Mt. Athos used to say that a more honorable person hasn’t stepped into that empire of solitude and soul for a long time.

One winter night, in the ”Velika Čukarica” tavern, by a burning furnace, Libero spoke about Chilandar and other monasteries of Mt. Athos to a curious group of young writers, to several poor fellows, who warmed themselves inside and drank one drink for hours, and always interested waiters. He knew all the monasteries and visited each one of them. It was a lecture about existence, about solitude, about human gifts, held by a great master, spiced with mystery.

He spoke mostly about the monastery of Esphigmenou, neighbor of Chilandar, a very beautiful monastery, surrounded by forests from three sides. It is on the seashore. It seems like a city discovered after many centuries. According to the legend, it was founded as early as the V century, destroyed several times until the end of the XIII century, then again rebuilt. The main church is dedicated to Christ’s Ascension.

The monastery was a sanctuary of ascetics, old men and martyrs who started on their path towards the saints. In their hair (Libero said), birds made their nests, and in their eyes, those who know could find answers to many otherwise irresolvable questions. Saint Anthony of Kiev was professed in the Esphigmenou monastery. He was able to walk above the tree branches as if walking on the most beautiful carpet and on the sea surface without wetting his feet.

Libero also spoke about the monastery of Stavronikita, about the Cathedral Church of this monastery, dedicated to St. Nicholas, at the very seashore, resembling a tower with the all-seeing eye, unusually beautiful. The icon with the image of St. Nicholas taken out from the sea, into which it was thrown during the times of iconoclasm, is kept in the church as a great sanctity. There are seventeen churches. It also has a rich library, where a curious man could easily get lost forever.

It was snowing heavily that night, nobody was breathing, there was not a single sound except the wind in the chimney and Libero’s voice.

Libero was also a pilgrim who visited monasteries in Serbia. He was a regular and always welcome guest in Visoki Dečani. He ran away there from himself and memories… The church gate opened before him in a special, protective way. There he would dive into his dreams, heal his own and other people’s wounds.

THE BIG TAVERN STAGE

This insatiable traveler spent most of his life in his Čubura, which is mentioned numerous times in his verses, reports, in paintings and drawings, always in a new, but somehow same way. Unintentionally writing his own legend, in the places of human goodness and imagination, in Belgrade taverns, where, except with wine, glasses were also filled with sorrow or joy, as the guest wishes, he was one of those for whom the tavern was never a place where one only eats or drinks and inordinately wastes his time. For such people, taverns were always open theaters, on which stages the newest, or in that moment created plays were performed, immediately evaluated, and only then, after the premiere, some of them eventually enlisted in our cultural heritage.

There is a bookstore in Čubura carrying his name, and a square of Makenzijeva Street, where one arrives and from which one departs into challenge and uncertainty. However, none of the taverns was named after him, which is an injustice.

Happy or sad, he was always easy, but never superficial. On the day before his death, in the eve of January 30, 1990, he wrote:

I will die when I anticipate I will die when I anticipate

behind the jalousie

with a caped guest

and without a drop of wine.

He will then flee

to faraway nests

to wait there for me

in white clothes.

It will be a beautiful fall.

The worshipped dead man. And in the name of everything,

the city will carry me on its hands,

like the last prince.

And into my beloved palace

they will rush in to take away

the weapons, the treasury, but in their fury

they will forget the aureole!

MICA, YOU DON’T LOVE ME

He worked in Borba for a long time. Times kept changing. At one time, that newspaper was a battlefield where the pens of giants fought, where the best names of journalism wrote, where all significant writers announced themselves, and our greatest drawers drew. On Saturdays, the poet and journalist Slobodan Marković, also known as Libero Markoni, gave it a special significance.

At that time, Borba was printed in eight hundred thousand copies. The irregular Saturday issue, awaited with impatience, arrived late on Friday. Today it may seem strange, but those were different times. On that day, a new article of Libero Markoni would be published, and each time it was something to remember. Itineraries, meeting unusual and significant people, not for the history of daily politics, of course…

It cannot be compared to any of the newspapers published today. From the pages of this newspaper, Libero watched you and went through his memories and his dreams for you. It cannot be compared to any of the newspapers published today. From the pages of this newspaper, Libero watched you and went through his memories and his dreams for you.

Wine, that curse and friend of vulnerable poetic souls, would sometimes take over him to such an extent that the worried editorial board decided to send him to Switzerland for treatment. The then editor in chief of Borba Slobodan Glumac accompanied him, an intellectual par excellence, translator of Bertolt Brecht’s poetry, one of the people who created a nest of creators and a point from which many talented people from the Borba editorial desk emerged.

During the trip, they stopped in Milan to complete some formalities in the Swiss consulate. Glumac left Libero in a restaurant, without a cent, ordered him lemonade and said he would come back soon. The formalities took longer than usual, so he returned only after several hours. He hurried, worried about Slobodan who didn’t speak Italian. When he entered the restaurant, he stopped astounded. Libero was sitting at a table full of wine bottles, and on the bar, with napkins over their hands, stood four Italian waiters. Libero would sing in Serbian ”Mica, you don’t love me…”, and the Italians would reply from the bar, also in Serbian: ”I doubt it, I doubt it…” This true story testifies about the incredible ability of Libero to get along with people, to force them to love him, to recognize in him a divine gift to which they would surrender.

***

A Completely Unintentional Legend

Slobodan Marković was born in 1928 in Skopje, where his father Dimitrije served as an officer of the Yugoslav Royal Army. His father finished his army service in Ljubljana and then moved to Belgrade with his family where he worked as a journalist in the Pravda newspaper until the end of his life. He wrote poems, short stories and novels, and in the year of his death, in 1938, he published a textbook on journalism The Craft of Being a Journalist.

Slobodan spent his childhood in Peć, with his grandmother Milica, a teacher, and grandfather Rista Protić, consul of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in Constantinople. He arrived to Belgrade, to his mother, during World War II, when Italians and Balists entered Peć. In the year 1943, he was imprisoned in the concentration camp in Smederevska Palanka. After the war, he graduated from the Second Belgrade Gymnasium, and then studied Yugoslav literature in Belgrade and Zagreb. During his lifetime, he published 62 books, while two, edited by his wife Ksenija Šukuljević-Marković, curator of the Museum of Theatrical Art in Belgrade, were published after his death (Southern Boulevard and Write it Down, Libero). Many of his books belong to poetic classics. He was also translator, journalist and painter, a bohemian.

He received Zmaj’s award in 1975 for his book Luka.

He died on January 30, 1990, and was buried in the Aisle of Deserving Citizens at the Belgrade New Cemetery, next to Miloš Crnjanski.

***

A Hundred Mad Lunches

He left so much behind him. Unforgettable poems, woven into the most romantic seductions of our youths. Itineraries whose magic makes plants and people blossom. Stories that cannot be forgotten. The most Belgradian Belgrade taverns have whole collections of his genre invention, drawings on napkins, with which he gallantly paid his bills when he was penniless.

However, A Hundred Mad Lunches of Libero Markoni, this triumph of Belgrade spirit and philosophy of life, glow above everything. The Čubura Bećarac, the Catfish of Mija Alas, the Summer Lunch under Zvezdara, the Lunch of Idle Teachers, the Silent Lunch, the Lost Paradise… The lunches where munching is allowed and courtship obligatory, the wine list refined and decorum set aside, lunches whose blessed epilogue was a cold watermelon or black Hamburg grapes from the well water, after which resting in the grass was allowed until the evening dew, or where there was singing or playing cards, or drinking and discussing Françoise Villon and fat Margot, or making a rumpus at the river bank and shrieking, lunches under a walnut tree in the yard or in front of a tavern… Until everyone feels the bizarre and endless lunch has come to an end, and that it is the final moment to depart.

|